When you join a support group for brain tumours, the first thing they say is

“Whatever you do, do not Google for information about your tumour.”

The reason is that you’ll find very little good news about gliomas on the web. If you are the kind of person to whom this advice makes sense, you should stop reading because there is no good news here either.

On the other hand, if you are the kind of person who’d rather know what you are facing so you can make plans, read on.

If there is bad news in my future, I want to know it. I understand that other people would rather not know too much about their situation and would rather leave their care in the hands of their medical team. That’s fine. You do what’s right for you and I’ll do what’s right for me. But if you want to learn a little about gliomas, read on.

I was diagnosed in March 2022 and I spent several hours every day for several months researching on The Google. I read every scientific paper and trial result that I could find.

About a year ago, I decided that I didn’t want my tumour in my head all the time (so to speak) and made a conscious effort to stop looking for information. I still think about it every day but it doesn’t dominate my thoughts like it did before. Now and again though, it sneaks back into my consciousness and I feel the need to write about it. So here I am.

What is cancer anyway?

As you probably know, cancer is not an external invader. It’s a bunch of your own cells that have malfunctioned. There’s usually a DNA copying error or mutation that causes a clump of cells to grow and divide more than they should. Errors like this occur all the time and our immune system has a mechanism for killing cells that misbehave. A message is sent to the broken cell — TIME TO DIE — and that’s usually the end of it. However, sometimes cells accumulate more mutations. For example, there might be a mutation that says ‘Ignore the TIME TO DIE messages.’ Another mutation might say ‘Forget you are a breast cell. Go hang out in the lungs for a while.’

Cancer is not just a single disease; there are over 200 kinds and they are all different. They are usually classified according to the body part where they started (e.g. breast cancer, lung cancer) or the kind of cell they started from (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma) or the name of the mutation that started the ball rolling (e.g., BRCA or ROS1) or even all three together. Although they have a lot in common, breast cancer and lung cancer are different diseases and if your breast cancer spreads to your lung, it’s still breast cancer.

When they are diagnosed, most cancers are given a stage that indicates how much they have grown and spread. The exact details of staging differ from cancer to cancer but, roughly, stage 1 cancer is contained within the organ where it started while stage 2 and 3 cancers are progressively bigger and might be detectable outside the original organ. If a cancer has spread to other organs, it is stage 4 and is often referred to as metastatic.

The original tumour is called the primary tumour. Tumours that appear away from the original organ are called secondary tumours or metastatic tumours or, among friends, just mets. For example, if you have metastatic lung cancer and it spreads to your brain, it’s still lung cancer, the original tumour in your lung is the primary tumour and the secondary tumour in your brain is called a brain met. If the tumour started in your brain, it is a primary brain tumour.

What kind of tumour do I have?

There are dozens of types of brain tumour. I have a glioma. It grew from a mutated glial cell.

There are two main kinds of cells in your brain. There are the neurons that do all the thinking and there are the glial cells. Glial cells (literally, glue cells) are like the infrastructure of your brain and they provide nutrients and support to neurons. A tumour that originates in glial cells is called a glioma. Cancer in neurons is rare in adults.

Unlike other kinds of cancer, gliomas are not given a stage — but they are given a grade. The grade of a tumour is a measure of how similar it is to a normal cell. A grade 1 tumour looks a bit different from a normal cell and grows more than it should. Grade 2 tumours look even more different and grow a little faster and so on until grade 4 where the growth is out of control and the cells look like undifferentiated mush instead of brain cells. Typically, the higher the grade, the faster the tumour grows so survival times are lower at grade 4 than grade 3.

Grade 1 tumours can usually be removed by surgery and that’s the end of it but higher-grade tumours usually come back even if all trace of the tumour is removed. They are typically treated with surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. Grade 2 tumours usually transform to a higher grade eventually and higher-grade tumours are considered terminal.

Tumours in other parts of the body are sometimes described as benign (not cancer) or malignant (cancer) but brain tumours are rarely described that way because even a non-cancerous brain tumour can kill you. If you have a benign tumour on your wrist, it might look ugly but it can get as big as a grapefruit and it still won’t kill you. A benign tumour the size of a grapefruit in your brain will kill you if it is not removed.

Radiographers can sometimes guess the grade of a tumour from an MRI but the grade is usually confirmed by a biopsy. The biopsy might be done as part of a craniotomy where most of the tumour is surgically removed at the same time but I had a needle biopsy. The neurosurgeon drilled a small hole in my skull and extracted a bit of tumour to analyse it. My biopsy was inconclusive but my tumour is probably grade 2 or 3. I have a very nice titanium plate now though.

Gliomas can be circumscribed or diffuse. Circumscribed means that the tumour has well-defined borders. Some people might have a circumscribed tumour the size of an orange (or a golf ball or a grapefruit). A circumscribed tumour causes problems when it grows so large that it puts pressure on the surrounding brain. This is called mass effect. The tumour squishes the brain and causes malfunctions. By contrast, a diffuse tumour infiltrates the brain. My tumour is diffuse. I imagine an ink drop spreading through water.

When I was first diagnosed, my neurosurgeon said my tumour was the size of two golf balls or half a hemisphere. My latest MRI says it is about twice the size now and has spread to both hemispheres.

Is my tumour treatable?

Several treatments for gliomas can extend a patient’s life but gliomas almost always grow back and eventually, the patient dies — though that might be many years later. For circumscribed tumours, surgery relieves the immediate crisis and radiation and chemotherapy postpone the day that the tumour grows back. However, there is no evidence that surgery is helpful for diffuse tumours.

Chemotherapy can be helpful but chemo sucks and — best case — it slows the growth a little.

My tumour is much too big for radiation.

There are several new drugs starting to become available now — especially target therapies. Chemo works by killing all cells that grow quickly (it kills them by damaging their DNA) but target therapies might block a particular protein that results from a mutated gene. For example, the glioma types astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma have a mutation in the gene IDH. The normal version is IDH-wt (wt = wild-type, i.e. the normal type) and the mutated version is IDH-mt. IDH-mt generates a defective enzyme which causes a bunch of other mutations and, ultimately, out of control growth. A new drug — vorasidenib — has just been approved which blocks that defective enzyme which prevents the tumour growing for a year or so. Vorasidenib is not approved yet in the UK — probably because it costs $40,000 per month.

So what’s the prognosis?

The correct answer is that no one knows. Unless your demise is imminent, the best your oncologist can give you is an average from patients from the past who have a similar diagnosis. They don’t usually make predictions.

On average, most patients with a grade four glioma survive between one year and eighteen months and around 5% will survive for five years. With grade three astrocytomas, it’s around 25% and with grade two it’s around 50% and most oligodendrogliomas survive much longer, regardless of the grade. Many factors affect survival times of course and some patients may survive much longer. But if you are a planning person, you should plan for less even if you hope for more.

Until a couple of years ago, there was a diagnosis — gliomatosis cerebri — that indicated a diffuse glioma in three or more lobes of the brain. Mine is in six. The incidence of gliomatosis cerebri is one in ten million so I am kind of special. I have a special friend in Canada who was also diagnosed with gliomatosis. We are both special! The prognosis (from the olden days) for gliomatosis was the same as for grade 4 tumours. But gliomatosis is no longer given as a separate diagnosis so maybe we are not special any more.

The numbers given for survival start from the day you are diagnosed. I was diagnosed in March 2022 but I have an array of undiagnosed symptoms going back many, many years.

In 2014, I had a grand mal seizure. I had restless leg syndrome about ten years ago. I had serious, serious vertigo during a moment of passion in 2000. I feel dizzy when I stand up. My first official symptom — phantom smells — began about two years before I went to the doctor to see whether I might have a brain tumour.

So when did my clock start ticking? Do they backdate the survival time if the diagnosis turns out to have been delayed?

The bureaucracy of dying

When I was first diagnosed, I thought it important to be prepared for an early death. I got all the paperwork done: wills, powers-of-attorney, a map of where all the treasure is buried, etc. I planned my funeral and made my funeral playlist.

The immediate period after a death is very stressful for the survivors because 1) The most important person in the world has just died and 2) There is a ton of bureaucracy stuff to take care of and difficult decisions to be made. Burial or cremation? Coffin or cotton shroud? Flowers? How do I get access to his pension?

Widows are probably the least equipped people in the world to deal with these issues and taking care of them ahead of time just makes so much sense.

There’s a brilliant site — GetYourShitTogether.org — that has checklists you can use to prepare. Someone will thank you for it one day. If you live in Bristol, have Dee at Divine Ceremony organise your funeral. Dee will make you smile more than you thought possible in a funeral parlour. She’ll also drive you to the cemetery in a white car and bury you in a white cotton shroud.

Our society has a huge phobia against talking about these topics and this causes real harm. Like, maybe, if I think of myself as a widow or — **shudder** — the deceased, it will jinx it and the Grim Reaper will visit even sooner. It won’t. Get your shit together. Someone will thank you for it.

After a while, talking about death loses its sting. At first, everyone recoils at the very suggestion that someone might be dying but after a while, you learn to talk freely about the aftertimes. It’s much healthier. We can even laugh about it now.

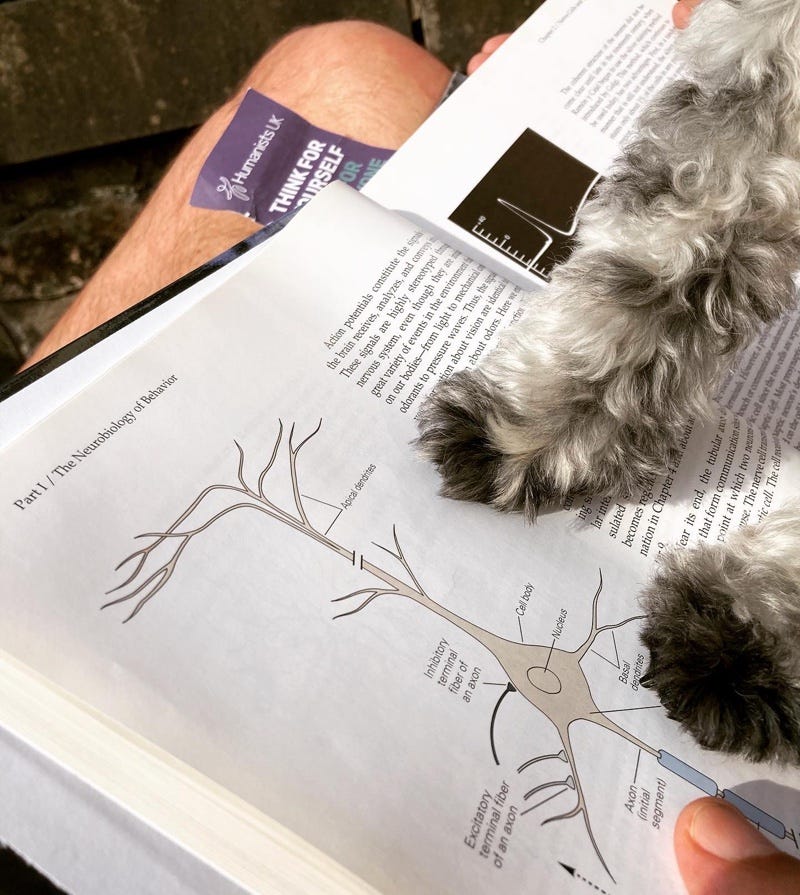

I have read a full description (at least that which you've shared in your blog) of your education and professional experience and did not see any mention of your ever taking any biomedical courses. Therefore I (a neuroanatomy major in grad school) was dubious about your actually having read a neurology text. Aha! Your photo gave you away. It seems highly likely to me that you got that little dog to read and to explain it to you.

Truly, I'm sorry that you too have cancer. Wouldn't wish it on my worst enemy if I had one. But a sense of humor stands a cancer patient in very good stead and thus you are well equipped to do the best possible.

Cheers!

I'm in awe of your positivity and humour Ragged, just amazing. And thank you for explaining this all so clearly, I actually had no idea about all the different stages and what those scary words meant. It's so much better for everyone that they're demystified, and that we talk about death more openly. I mean we're all going to get one. I just wondered about the phantom smells - how did you know this was a symptom, and what is that, just one of the brain's freak outs?